Historically, Kathak dates back to Vedic times, when the epics of the Rig-Veda, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana were composed. The word Kathak, story teller, derives from ‘katha’ which means story. Communities of Kathaks wandered around the countryside conveying the stories of these great epics and myths to the people by means of poetry, music and dance, all three of which were closely linked. The chief aim of the Kathaks was to instruct the indigenous population of the subcontinent in the knowledge of the gods and mythology of the Aryans. This means of instruction has a parallel with the early Greek theatre and with the beginnings of English drama. Indeed, the link is more than superficial, for all Indo-European languages, myths, legends, rituals, superstitions and sex symbols can be traced back to the common Aryan source.

In the fifth century B.C. there arose in North India a new religion which was, to begin with, very different from the Vedic religion then prevalent. It was founded by Prince Siddharta of the Sakya tribe who, forsaking riches and power, preached equality among all men and by his own example showed the path to self-realization. He came to be known as Buddha or the Enlightened One and his teaching spread in due course, especially under the saintly king, Ashoka, to most of the countries of Asia. Buddhism was a Spartan religion in comparison with the Vedic rituals of the Brahmins. It called for the simple life because according to it, the greater the detachment from the world and its temptations, the nearer was the source of enlightenment. This new religion involved no gods and no elaborate worship of them. Therefore, it did not need to employ the arts, all of which had hitherto been connected with religion. Buddhism was propagated through monks and nuns who had taken vows of poverty and chastity and who devoted their lives to social service with an almost Christian dedication. Religious dancing like that of the Kathaks was irrelevant to its needs. Nevertheless, Buddhism tried neither to stamp out Hinduism nor campaigned actively against the Kathaks, who continued to practice their art. It was not until much later, when Buddhism became a sect of Hinduism and the Buddha himself was enthroned in the Hindu pantheon as an avatar of Vishnu, that it used the arts of painting, sculpture, music and dancing.

After Alexander’s incursion into India in 326 B.C., the northern part of the subcontinent was subjected to the invasions of the Scythians, the Kushans, the White Huns and the Gurjaras, all of whom came through the mountain passes in the North-West. Each of these peoples left the imprint of their racial and cultural characteristics on the population of Northern India. This constant influx was bound to weaken the structure of the caste system carefully laid down by Manu for the consolidation of Brahminism. The increasing struggle for dynastic power led to an emphasis on temporal and military matters, and for this reason the Brahmins did not exercise the same control over society as they were able to in the South. The patronage of the arts must also, to some extent, have passed from religious leaders into the hands of kings and princes, although the themes would undoubtedly still have found their inspiration in the scriptures of the Hindus.

The population of the Indo-Gangetic plain had by this time undergone considerable racial change and it is fair to assume that the classical dance of this area too must have been modified and enlarged according to the new characteristics of its ethos.

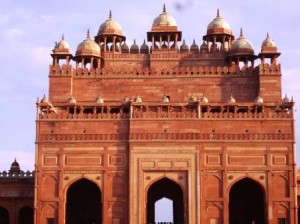

From the eighth century the new dynamic force of Islam appeared in the subcontinent. It was brought first by the Arabs and then, in a more permanent form, by the Turks. For over a millennium, in spite of the many invasions which had taken place during that time, Indian society had not been called upon to adjust itself to so radically new a situation. Here was the complete antithesis of the caste system. Islam preached that all men were brothers under One God, that there was only one path to heaven which lay through the teachings of the Prophet, and that it was morally dangerous to make representations of living things. This attitude was seriously to affect Kathak dancing, which was not only concerned with many gods and goddesses but also portrayed them in human form. This made the dance doubly sacrilegious to the Muslims and therefore it was vehemently condemned. The Kathaks had to find Hindu patrons, often Rajput princes of Central India, or disperse into the countryside where they could safely continue to dance in their traditional manner. With the passage of time, under less severe rulers, these Kathaks were to be permitted once more to dance with impunity.

Muslim society was based largely on merit and even slaves could aspire to kingship, but the caste system of Hinduism had at this time become stratified and effete. It had no equipment to counteract this new element of fluidity which was so rapidly forcing itself into society from without. The temper of the times had however, long been conducive to new movements, both in the Hindu and Muslim religions. In Islam it took the form of Sufism and later, in Hinduism, of Bhakti. Both were mystical in intent, preached toleration, and practiced devotion to God and service to humanity. The best minds in Islam were attracted to Sufism. It was as the indirect result of the tremendous influence of the teachings and poetry of the Sufis, that later Muslim monarchs became tolerant of, and even encouraged and fostered the Hindu arts. The Bhakti movement, on the other hand, which matured into fullness later than Sufism, strove to mitigate the inequalities of the caste system by stressing the brotherhood of man and of God’s love for all human beings irrespective of religion, caste or social background. It was this great synthesis of the quintessential best in both Hinduism and Islam, that produced Bhaktas like Kabir (1440-1518), who was born a poor Muslim weaver in Varanasi and who became the generative source of great poetry and music.

The Kathak dancers used much of the Bhakti-inspired poetry for the nritya parts of their performances. This poetry was intensely emotional and declared the poet’s love for God in personal terms.

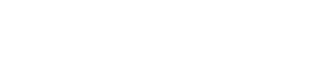

The rise of the Vaishnavite cult which came before the Bhakti movement, had an important bearing on the development of Kathak. This embodied the worship of Vishnu, the god of preservation in the Hindu pantheon. In his incarnation as Krishna he was the chief subject of music and dance. There are understandable reasons for the Lord Krishna’s long-sustained popularity with the common man throughout India. His romantic love for Radha symbolized the love of God for Man in terms which were simple and immediate. He was, moreover, always depicted as an engaging young man of dark complexion, and as such represented a major concession by the fair-skinned Aryans to the original dark-skinned inhabitants of the Indian subcontinent. Krishna, therefore, represented the synthesis of the Aryan and Dravidian cultures. His warm human qualities made it possible for people to identify themselves with him without feelings of blasphemy or sacrilege. His mischievous audacity evoked delight not fear, love not awe, and so lent itself admirably to presentation in dance form.

The Krishna stories also have a serious aspect. In the Mababharata, Krishna appears to Arjun as his charioteer and discourses with him on his duties as a warrior, as a statesman and as a man seeking the truth. Krishna’s main teaching was that duty (Karma), however unpleasant, must come before all else and man must endeavor without hope of reward.

All these episodes were excellent subjects for poetry, music and dance, which, in Vaishnavism, were important means of worship. There are, therefore, many famous poets, musicians and dancers connected with this cult. It reached its culminating point in the twelfth century with the poet Jayadeva, author of the Gita Govinda, who composed numerous keertans or devotional songs, and whose wife expressed them through dance. Later the poet-musicians Chandidas, Tulsidas, Mira, Vidyapati and Surdas carried on this tradition. Much of their poetry incorporates actual dance-syllables known as boles. This clearly indicates that dance was an essential of such hymns and neither was complete without the other.

The Muslim religion, as we have seen, excludes such arts as sculpture, painting, music and dance as forms of worship and these arts have no place in Islamic religious ritual. So when the Muslim influence established itself in India, this attitude had a profound effect on the hitherto Vaishnav-dominatcd Kathak. Because of its religious connections the early Muslim rulers, regarded this indigenous form of dance as unsuitable for their patronage, but they were by no means insensitive to the pleasures of music and dancing when divorced from religion. The result was that they sent for musicians and dancers from Persia and Central Asia. These dancing girls were known as domnis, hansinis, lolonis and hourkinis. Each of them had their own distinctive style of dancing.

Now as we have already seen, this was not the first cultural contact between India and the lands lying to the north-west. There had been rapport between them for many centuries. Musical modes from Persia such as Yamani and Kafi were incorporated into the Indian raga system at the time of Amir Khusro, who lived from the mid-thirteenth to the early fourteenth century. His genius touched not only music, but literature as well and so contributed towards the synthesis. Consequently the dancers and musicians were easily able to absorb those features of the Indian arts which they considered would be acceptable to their patrons. The few Hindu dancers who found their way to the courts were, in their turn, influenced by the new styles. This apparent secularization was to have a significant extension in the later Mughal period of Indian history. The Mughals brought political unity, economic stability and social justice. They took an intensive interest in, and fostered the Indian arts. The flower which resulted from the Islamic seed sown in the rich soil of Hindustan, displayed the color of both cultures. The lotus had met with the rose.

With the growing stability in government came a new affluence which was reflected in every aspect of life. Dress at court was of course, modeled on Persian styles and the court dancers too adopted the costumes of the day. In the last few years of Akbar’s reign there is evidence that dancers, both men and women, wore an interesting new costume. The men wore a jacket, and the women a choli, a fitted blouse with short sleeves which leaves the midriff bare. Both had tight trousers called a ‘chudi pajama’. Over these they wore plisse skirts made of stiff material in three tiers the longest of which reached several inches above the knee. These skirts bear a remarkable resemblance to the tutu of Western ballet which was not invented until very much later. They also wore, over their shoulders, a transparent scarf of silk or muslin, known as an ‘odhni’ or ‘dupatta’. The head-dress consisted of a muslin turban.

In the time of Akbar’s son Jehangir, the dancers adopted the dress which was popular in the early part of his reign. The popularity did not last long at court, but whereas the fashions of the nobility changed, the dancers retained this costume and it has been in use ever since. It consisted of the ‘chust pajama’ in a bright color over which was worn a high-necked diaphanous dress called the ‘angarkha. The soft, flowing, bell-shaped skirt was of full length and, like the sleeves, was left unlined. For women, an embroidered waistcoat of rich satin emphasized the body line. Men wore a double-breasted ‘angarkha’ which fastened on the left, with their ‘chust pajama’. The women also wore a gossamer ‘odhni’. The palms of their hands and bare feet were dyed with henna. Numerous miniatures of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries show dancers in this costume. Its advantages, so far as the Kathak dancers were concerned, were that the full skirt fanned out at every fast movement, accentuating the fluidity of the dance, and yet was transparent enough to reveal the outline of the figure and perfection of the pose when the dancer was still.

The Dhrupad style of music is essentially religious and had been connected with Kathak since the late fifteenth century. It came to its peak with the genius of Tansen during the reign of Akbar. This mode is dignified and majestic and has no room for frivolous ornamentation. The poetry is chaste and uplifting, using similes of sixteen selected flowers, fruits, birds and animals, four of each. As these similes adorn the music, so in Kathak, they serve to embellish the bhava, which is the language of gesture for the expression of various moods. With the emphasis on nritta, however, and the absence of religious themes, this music was used less and less in later times, until it became the convention to use just a single phrase of music, called the lehra. The lehra was convenient because, as it was repeated over and over, it did not distract attention from the rhythmic variations of the dancer and drummer.

The decline of the Mughal Empire and the rise of European power saw the gradual decadence of Kathak. Most of the petty princes and warlords had little appreciation of the fine arts and so Kathak degenerated into voluptuous and sensual styles. Although there was an attempt to retain the basic graces of Kathak, the tendency was increasingly towards lasciviousness, and the performers became notorious as women of easy virtue. It was this debased form of Kathak which the European adventurers called ‘nautch’, which was a corruption of the Indian word ‘naach’ meaning dance.

The true spirit of Kathak, however, survived in spite of these social stigmas. High caste Hindu girls, especially in Rajasthan and Bengal, had to be accomplished in the arts in order to make a good marriage. They were therefore tutored at home, often to very high standard, but their attainments were reserved exclusively for the pleasure of the family.

The first dancer of genius to break this embargo was Menaka. Her achievements were truly outstanding – trained under the best gurus, she revived Kathak as an entertainment worthy of public support and what is more, she gave to it the imprimatur of social acceptability in its homeland, and also introduced it to other countries.

Menaka first formed a residential school of dancing at Khandala in 1938, and gathered together some of the best teachers in each style. Her main interest was in exploiting the possibilities of Kathak in productions of ballets. In this she was helped by Dr Raghavan, Karl Khandalawala, Maneshi De, Ram Narain Misra, Vishnu Shirodkar and Ram Chandra Gangooly. She produced three ballets in which she employed pure Kathak techniques, discarding the lehra and using classical music skillfully blended to complement the ballet themes. Deva Vijaya Nritya is about Vishnu’s transformation into the beautiful Mohini in order to rescue the Amrita or elixir from the demons. The second part of this ballet tells of how Shiva fell in love with Mohini and how he went into tapasya, meditation, so that he might regain his self-control. Krishna Lila deals with the life of Krishna in Vrindaban and how Radha fell in love with him. The third ballet, Menaka Lasyam, is the story of the sage Visvamitra’s attempt to gain immortality through tapasya, and of how the god Indra sent an enchanting apsara, Menaka, to tempt him and so interrupt his meditation. Menaka’s fourth and most important ballet was Kalidasa’s Malavikagnimitram. In this she employed for the first time, Kathak and Manipuri as well as Kathakali techniques. Her friendship with Pavlova was a constant source of inspiration to Menaka, and of great help to her in staging these ballets.

Today, there are two main branches of Kathak, named after the cities in which they took shape and flourished. These are the Jaipur and Lucknow schools. These schools or gbaranas have their own distinct personality which was imparted to them by different gurus. Very often the traditions of the gharanas were sustained by succeeding generations of the same family. This gharana system also prevails in music, both vocal and instrumental.

The Jaipur style developed under the patronage of the Rajput rulers of Rajasthan and has a very strong religious flavor. One of the founders of this school was Bhanuji, a devotee of Shiva, who is said to have been taught by a saint. The greatest contribution to this style was made jointly by the brothers Hari Prasad and Hanuman Prasad, descendants of Bhanuji. Hanuman Prasad was a very religious man and it is said of him, that once at the festival of Holi he arrived late at the temple and the doors had been shut for the night. Nevertheless, his devotion was such, that he danced in the courtyard outside. At the climax of his dance, the temple bells within came miraculously to life and the doors burst open of their own accord. Even if this story is apocryphal, it is an indication of the power of this guru’s dancing.

A more recent name is Jai Lal, another descendant of Bhanuji. Jai Lal started dancing at an early age and was highly accomplished in the two percussion instruments, the pakhawaj and the tabla. It was due to this, that his dancing was famous for its rhythmic quality. He included long parans, which are pure dance pieces set to subtly varying syllabic beats of the pakhawaj. His partiality for pure dance is evident to this day in the dancing of the exponents of the Jaipur gharana.

Sunder Prasad, the younger brother of Jai Lal, is the present guru of this school and teaches at the Bharatiya Kala Kendra in Delhi.

There is a minor off-shoot of Kathak not widely known, which appears to have been connected at one time to the Jaipur gharana. It was founded by Janki Prasad of Jaipur, but its adherents settled in Varanasi and Lahore. The main differences between this branch of Kathak and the two major gharanas are that it stresses clarity of line and execution even if this means sacrificing speed, and whereas, for footwork, the Lucknow and Jaipur gharanas allow the use of percussion instruments, here the dance syllables only arc permitted. Its exponents at present are the brothers Sohan and Mohan Lal, Nawal Kishore and Kundan Lal.

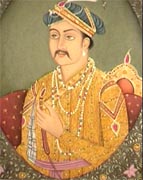

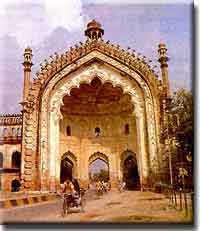

The Lucknow gharana matured into a distinct and individual style at the time of Wajid Ali Shah, ‘Akhtar’, the last Nawab of Avadh. By the end of the eighteenth century, the Mughal Empire had declined to such an extent that the Governors and tributary Nawabs and Rajas were independent in all but name. Delhi had been the centre of culture. All the arts had had full scope and flourished in rich profusion. With its decline, its poets, musicians and artists gradually began to leave. In Avadh the Nawabs now saw an opportunity to transfer its glories to their own capital, Lucknow. The migrants from Delhi were welcomed and given pensions and grants, and a new centre evolved. Lucknow became synonymous with elegance and aesthetic appreciation. When Wajid Ali Shah ascended the throne in 1847 at the age of twenty, the court circle already included artistic protégés of all kinds. He was by nature inclined towards the arts and resolved to outshine all his predecessors. The young Nawab devoted himself to this end with an energy which now seems suicidal. He spent twenty million rupees on building the famous Qaisar Bagh palace, the Imperial Garden palace. He established a centre for the training of dancers known as “Pariyon ka Khana’ or ‘House of Fairies’, because all the girls were selected for their beauty. He surrounded himself with famous poets of the day who wrote in Urdu as well as Persian, and was himself a prolific writer of verse, a competent musician and a dancer. His dance guru was Thakur Prasad whom he respected so much that he elevated him to the highest seat in the court.

Inder Sabba which resembles the Sanskrit classic Vikramorvasia returned, perhaps unconsciously, to the original concept of Hindu drama, where poetry, dance, music and costume were equal members of the same body. The play also brought back to Kathak after many centuries, its element of natya and led to a wide extension of bhava.

Wajid Ali Shah’s passion for these arts was carried to a point where he neglected his state duties. This lack of interest in political affairs made it possible for the English to annex his kingdom and he was sent into exile.

The last outstanding patron of Kathak was Raja Chakradhar Singh of Raigarh. He too was a dancer and musician and his patronage extended to all dancers irrespective of their gharana. Jai Lal of Jaipur and Achhan Maharaj, the eldest son of Kalka Prasad of Lucknow, both served him for many years. He encouraged and nurtured young talent wherever he found it.

The Raja’s fate was almost identical with that of Wajid Ali Shah, and for the same reasons. He was forced to abdicate in favor of his son and deprived of the means to indulge his interests, died a broken man about twenty years ago.

There are three main gurus of the Lucknow gharana, Lachhu Maharaj, and Shambu Maharaj, sons of Kalka Prasad, and Birju Maharaj, the son of their eldest brother Achhan Maharaj.

Lachhu Maharaj (1901-1978) taught Kathak in Bombay and has choreographed many ballets, the most important being Malati Madhav, which the Bharatiya Kala Kendra invited him to choreograph and produce. It was first presented at the Sangeet Natak Akademi Dance Seminar in 1958. He is an outstanding choreographer and has experimented with adopting Kathak for Indian films. Lachhu Maharaj was acclaimed for the choreography of dance sequences in movies like Mahal, Mughal-e-Azam and Pakeezah as well as his ballets like Goutam Buddha, Chandravali and Bharatiya Kissan. He was also the founder Director of the Kathak Kendra started by the Uttar Pradesh Government in Lucknow. Among many prestigious awards he won were the Presidents’ Award and the Sangeet Natak Academy Award.

Shambu Maharaj and Bjrju Maharaj both taught at the Bharatiya Kala Kendra in Delhi, where many of their pupils were Government of India scholarship holders. This school was a result of the efforts of Nirmala Joshi, whose great dream it was to form an institution where the best teachers of Kathak and Hindustani music could train suitable pupils and, at the same time, experiment in ballet productions. She finally succeeded in 1952 when the Bharatiya Kala Kendra came into existence.

Shambu Maharaj is a great exponent of bhava and has revived many thumris and bhajans. He has the distinction of holding two of the highest awards in Indian art. Hundreds of dancers have been trained by him, among the best known of whom are Bharati Gupta, Damayanti Joshi, Gopi Krishan, Kumudini Lakhia, Maya Rao and Sitara Devi.

Birju Maharaj’s efforts are directed towards adapting Kathak ballet for the modern stage. This presents an interesting challenge, for the theatres today contain a very much larger audience than was ever possible in either the temple courtyard or the intimate atmosphere of the Mehfil, the select company of connoisseurs. The choreographer must communicate delicate nuances and at the same time provide movement on the stage. The music for his highly successful ballets Kumara Sambhava, Shan-e-Avadb and Dalia was provided by the two Dagar brothers.

The stage settings and costumes were especially designed as these were period pieces. For ballets set in the early Hindu period the women wore a sarong-like skirt which was a little above ankle length. This allowed full freedom of movement and at the same time made it possible for the footwork to be seen to advantage.

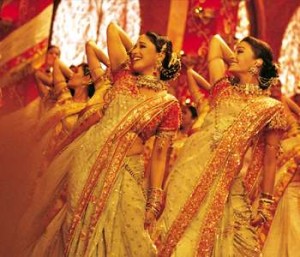

Kathak dancers today have considerable freedom in their choice of costume, as a wide variety of permissible styles arc in use. Broadly speaking these are either Hindu or Muslim inspired.

Among the Hindu costumes the oldest and that which is most generally used is the ‘ghaagra and odhni’. The ghaagra is a long, very full, gathered skirt with a broad gold or silver border. Narrow silver or gold bands radiate all the way from waist to hem. The rich colored silks used for the ghaagra must not be so heavy as to hinder the dancer during fast dance movements. The choli, worn with the ghaagra, is usually of a contrasting color and has embroidered sleeve-bands. The light, transparent odhni is interwoven with gold patterns and draped over the head and left shoulder. The jewellery worn with this costume is rich and varied. Bracelets, armlets and necklaces are of gold. The heavy ear-rings, also of gold, are set with precious or semi-precious stones. Their weight is taken off the ear-lobes by fine gold chains or, more usually, ropes of tiny seed-pearls which hook into the hair. A jewelled ‘tika’ is suspended in the middle of the forehead.

The Hindu costume for men consists of a silk dhoti with a brocade border. This is draped round the waist and between the legs to give a loose trouser-effect. A silk scarf is tied round the waist. The upper part of the body is left bare except for the sacred thread which is always worn, though sometimes a loose fitting jacket with short sleeves may also be worn. The jewellery is elaborate and consists of a wide gilt necklace with stones and a variety of smaller necklaces. Small pieces of gilt jewellery in a traditional pattern are mounted on cloth. These are tied round the wrists and arms.

The Muslim costume, as we have seen, was added much later, but has become so popular and so closely associated with Kathak that many people really believe that this is a Muslim dance brought from Persia by the Mughals. The costume is still essentially the same as it was in Jehangir’s time, except that the skirt of the angarkha is now shortened to calf length. The jewellery worn with it is necessarily delicate and light, so as to be in keeping with the gossamer effect of the angarkha. The earrings are plain gold rings, each with a drop pearl and two smaller stones on either side. Two rows of pearls may be worn round the neck. Armbands and bracelets are of gold or silver filigree decorated with colored stones. Sometimes an unusual hand ornament is worn. This is basically a circular jewelled ornament for the back of the hand and is kept in place by delicate jewelled links attached on one side, to a bracelet round the wrist, and on the other, to five rings worn one on each finger and the thumb.

A Jhumar or Chapka is an ornament for the head which may also be worn. This is a fanshaped piece of jewellery which rests flat on the hair. The apex of the triangle lies near the parting and the delicate jewelled ‘ribs’ of the fan shape radiate forwards to rest flat on one side of the head.

Indian films have used dances which were supposed to be Kathak, but are best described as having drawn some inspiration from Kathak. The discrepancy arose not necessarily because the dancers did not know Kathak, for some such as Sitara certainly did, but because directors had to take into account the tastes of the ‘groundlings’ who are not interested in subtleties. Kathak also lives in the collective memory and imagination through its vibrant portrayals in Hindi cinema such as Mughal-e-Azam, Pakeezah, Umrao Jaan, Devdas and others. Apart from these exceptions Kathak has generally suffered at the hands of film makers.

A medium which should prove excellent for Kathak as a solo dance, is television. It is ideal for conveying to the audience the delicate bhava and abhinaya of the artiste. Skilful direction and camera work with close-ups of the eyes, the facial expressions, the hands and the feet could, possibly, add a new dimension to Kathak. Moreover, television functions in an intimate atmosphere and the dancer could easily produce the feeling among viewers that the performance was directed to each one individually.

As far as the theatre is concerned, on the other hand, it would seem that the future of Kathak lies in ballet, where its rich and varied repertoire of nritta, nritya and natya can be fully exploited.