The name Avadh (Oudh) was derived from the popular version of the ancient town of Ayodhya, which was the capital of the mythological kingdom of Raja Dasharath in prehistoric times. Sravasti (ancient Savatthi), also of this region, and where Gautam Buddha spent many years, features in the Buddhist literature of the centuries immediately preceding the Christian era. In the fourth century A.D. it was part of the Gupta Empire, after which it seems to have become a wilderness, being deserted, by the seventh century A.D. It is believed that in the following century the Tharu tribe from the foot of the Himalayan mountains descended upon this area. By the ninth century A.D. the whole area had become part of the Kingdom of Kanauj. Two centuries later, in 1194 AD., Kutub-ud-Din finally defeated the ruler of Kanauj and broke up the last great Hindu Kingdom of this region.

The region saw many vicissitudes and changed hands many times. In 1555 A.D the Mughal King Humayun emerged as the final victor and the area thus became part of the Mughal Empire. His successor, Akbar, created the Suba (Province) of Avadh as one of the units of his Empire, the Governor of which was called a Subedar, and the official name of the town of Ayodhya also became Avadh.

Avadh was at that time divided into five havelis or districts: Avadh (Faizabad), Gorakhpur, Bahraich, Lucknow and Khairabad. These boundaries seem to have remained unchanged until the reign of the Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah. He appointed Sadat Khan as the Subedar of Avadh in 1722 A.D. This may be regarded as the date of the founding of the dynasty of the Nawabs of Avadh, which ruled until 1856 A.D. With the disintegration of the Mughal Empire Avadh achieved defacto independence.

The first three rulers of Avadh were Sadat Khan. Safdar Lang and Shuja-ud-Daula. The last mentioned was obliged to give away certain areas of his dominion to the East India Company and his successors continued to cede parts of their Province to the British in exchange of various treaties. In 1775 A.D. Asaf-ud-Daula came to power and was succeeded by Sadat Ali Khan who too lost some more area to the British. From then on the dynasty continued to rule under the protection of the British and in 1856 A.D. Avadh was annexed to the British Raj when the last Nawab Wajid Ali Shah surrendered his crown to the British and left for Calcutta.

The Lucknow gharana of Kathak dance developed during the reign of Asaf-ud-Daula (1775 A.D.- 1798 A.D.) and Wajid Ali Shah (1847 A.D -1856 A.D.). As seen earlier the Kathaks who danced had their centres in Ayodhya and Benaras. The Rasadhari tradition flourished around Mathura and Braj. The contemporary Kathak’s line of teachers extends backward beyond the Muslim period in ancient times. James Prinsep’s 1825 census of Benaras discloses that there were more than a hundred Kathak castes in the city at that time. F. Buchanan’s survey of Bihar during the years 1807-1814 reports fifty-eight Kathak establishments in the principal towns of the area. At this time the profession was mature and its representatives were widely distributed in North India.

With the patronage received from the Nawabs of Avadh, Lucknow soon acquired fame as a centre of art. We gather from the descendants of Kalka-Bindadin, the famous Kathak exponents of Lucknow gharana, that their ancestors hailed from Handiya, a village in Allahabad district. Prakashji who moved from Handiya with his ancestors and came to Lucknow and sought royal patronage under Asaf-ud-Daula. Prior to that also there is evidence to prove that Kathaks and their Muslim rulers did meet and they had intimate dealings with each other. Ghazi Miyan, a Muslim saint whose cult is prominent in Benaras, is often worshipped by the Kathaks. In his commentary on Bhaktamal, Priyadas tells a story of a Hindu dancer’s contact with Muslim authority. Narayan Das.a dancer who danced only before the idol of Hari, was invited by the Muslim ruler of Hariya Sarai to perform before him. Narayan Das put tulsi garland, a symbol of Hari, before himself to avoid the crisis and performed before the Muslim ruler. Priyadas “wrote his commentary on Bhaktamal about 1712 A.D. We may, on this literary evidence, conclude that the contact by this time between the Muslim patrons and Kathak dancers was well established. Some scholars also suggest that Hariya Sarai may be Handiya village.”

The late court of Avadh was the final example of oriental refinement and culture in India. Among many accounts of the splendor of Lucknow, “Hindustan Men Mashriqi Tamaddun Ka Akhari Namuna” by Abdul llalim Shararu stands out for the details of the social and cultural life of the period of the Nawabs’ reign in Avadh. It mirrors it in many colors giving glimpses of a culture which was in its last phase. The pattern of life in Lucknow began to evolve in the magnificent era of Mughal power, in the sixteenth century Delhi during the reign of Akbar. After the Mughal Empire began to disintegrate in the early eighteenth century, certain leading figures left Delhi and eventually found a new home in Lucknow, where the independent court of Avadh (Oudh) had been established in 1753 A.D. The highly developed culture was further refined in Lucknow to a level of splendor and sophistication scarcely paralleled in any other Indo-Islamic society. The high culture of Lucknow was in full bloom from the last quarter of the eighteenth century until the collapse of the Lucknow monarchy in 1856 A.D. And it actually survived as long as the feudal system survived in U.P. till the British left India in 1947.

Life in Lucknow was sweet and gracious, free from worldly cares and anxieties, a life of affluence, devoted to luxuries and leisured activities. The nobility controlled great wealth through the feudal system and spent lavishly; so did the comfortable middle class which was connected with the nobility at various levels. Some accounts suggest that even the peasants led a fairly comfortable life; those who had difficulty in earning a living simply had to look for a patron. They were appreciated for their skills.

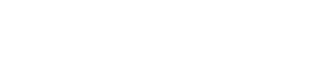

These accounts cover an astonishing variety of topics: religion, education, medicine, ceremony and social etiquette, dress, culinary arts, calligraphy, dancing, popular language and art of story-telling, such pastimes as kite- and pigeon-flying and the arts of combat and defense, the development of the Urdu language and its prose and poetry, architecture, music, theatre and other forms of public entertainment. Asaf-ud-Daula spent money in satisfying his desires for voluptuous living and on the embellishment and comforts of the town. His one desire was to surpass the Nizam of Hyderabad and Tipu Sultan and his ambition was that the grandeur of no court should equal that of his own. He built magnificent buildings and monuments among which his Imam Bara is incomparable. The Rumi Darwaza still evokes admiration for architecture. He lived in the Daulat Khana near Machi Bhavan and the Imam Bara. In order to indulge in his pleasures and be away from the crowds and worldly affairs he had built Bibapur Palace outside the town. There was already in the times of Shuja-ud-Daula an enormous influx of musicians and troupes of singing courtesans into Avadh and Lucknow. Besides these, the Kathaks from Ayodhya and Benaras were attracted to the court. The foregathering of these people advanced the art of the dance and gave it great local importance. Sharar refers to two groups of male dancers in Lucknow: the Hindu Kathaks and Rahas dancers (rasdharis, who specialized in the Krishna lila), and the Kashmiri Muslim bhands. The real dancers were the Kathaks and the Kashmiri dancing troupes. They had introduced young boys who wore their hair long like women and danced with animation and vivacity at times arousing the spectators. At the time of Shuja-ud-Daula and Asaf-ud-Daula. there was one Khushi Maharaj. Hallalji, Prakashji and Dayalji lived during the time of Nawabs Sadat Ali Khan, Ghazi-ud-Din Haider and Nasir-ud-Din Haider. However, it appears that Prakashji was in the court of Asaf-ud-Daula and his sons Durga Prasad and Thakur Prasad were famous court dancers in the time of Wajid Ali Shah. It is said that Durga Prasad taught Kathak to Wajid Ali Shah. The two sons of Durga Prasad, Kalka and Bindadin, became famous and no one in the whole of India could rival either of them at dancing. So great was their art that they became legends in their own lifetime.

The flowering of the Lucknow gharana of Kathak is ascribed to these dancers. The older dancers achieved fame because of some particular aspect of the art, but the two brothers Kalka and Bindadin were masters of every aspect of the dance. Kalka Prasad’s specialty lay in his mastery of rhythm. Bindadin was gifted with poetic leanings and was a great composer. Together they shaped the Lucknow gharana by the attributes it has come to be known — lyrical and precise. The graceful quality of Kathak was explored by these two brothers in a fantastic manner.

Bindadin was a great devotee of Krishna and his innumerable compositions in praise of the Lord are a living testimony to his genius as a composer and a vaggeyakar. Thumris, dadras and Bhajans written by him became part of Kathak in the abhinaya section. Kalka Prasad was an inimitable tabla player and had specialized in layakari. He died a few years earlier than Bindadin. He had three sons, viz.. Acchan Maharaj, Lacchu Maharaj and Shambhu Maharaj who were the greatest contemporary Kathak exponents in the present century. The Lucknow gharana owes its beauty to them.

It was during the reign of Wajid Ali Shah, the last Nawab of Avadh, that Lucknow gharana received a great impetus. Wajid Ali Shah’s own contribution to Kathak is historic and noteworthy. Though he was given to pleasures he was exceptionally gifted. An accomplished musician and dancer he patronized the art of music and dance. He wrote poetry in Urdu and Hindi. It is said that he introduced the form of thumri in music and dance.

Wajid Ali was very much interested in architecture and built Kaiser Baug and a large oblong enclosure of elegant and imposing two-storied houses. The inner courtyard of the Kaiser Bang with the lawns was called Jilo Khana, the Front House. In the centre was a Barah Dari which is now Lucknow’s Town Hall. Outside the Kaiser Baug were many royal houses which made this plot of land one of the wonders of the age. These buildings were outside the eastern gate of the Kaiser Baug. After Chini Baug, the Chinese garden, there was Jal Pari, the Mermaid Gate. The Vazir Nawab Ali Maqi lived near this gate so as to be always near the King and within immediate call if necessary. Wajid Ali Shah had met him at the house of Azim-ud-Daula where he used to go to see the courtesan Waziran. Wajid Ali Shah was attracted by Ali Naqi’s youthful cheerfulness. Among other important buildings was the Chau Lakhi building bought for four lakh rupees, in which lived the King’s chief wife Nawab KhasMahal. Wajid Ali Shah gave titles to his favourite wives who were given their own palaces.

Wajid Ali’s thumris were composed under the name of Kadar Piya or Akhtarpiya. At the time of Kaiser Baug fairs at the foot of an enormous shady tree Wajid Ali Shah used to dress himself up as a yogi in red-colored garments and sit there. More than eighty lakh rupees were spent on the Gateways and the houses of the ladies of the King. Once a year during the fair the public was admitted into Kaiser Baug and they could see a voluptuous style of living to which the King was addicted. He had seen the Rasalilas, the theatrical presentations of Shri Krishna’s dance, and was so pleased with Krishna’s amatory dalliances that he devised a drama about them in which he himself played the part of Kanhaiya-Krishna and decorous and virtuous ladies of the palace acted as gopis, milkmaid lovers of Krishna. There was much dancing and frolicking. He had made special arrangements for the training of the ladies and courtesans in dance and had a section called Pariyon-ka-Khana. These dancers were then asked to take part in the Rahas. The Rahas was based on the Rasalilas that he had witnessed. Wajid Ali Shah took great care in choreographing the Rahas. This could he seen from the stage and scenario records of his time.Entries of the artistes on the stage and the exposition of the roles along with the methods of unfolding the plot are clearly indicated. Describing one of the group dance sequences of the gopis he has even noted that while standing in two rows, the shorter girls should occupy the first row. He used solos, variations and divertissements and decorative accessories in the weaving of the plot. Once he made a successful beginning with the Krishna theme, Wajid Ali Shah introduced other performances also which, though based on Indian tradition, were steeped in Persian imagery. The impact of the Rahas was so overwhelming that any stage production on a large scale was termed Rahas in spite of its varying themes. In this direction the King’s contribution was indeed of a great significance. With the opening of the gates of the Kaiser Baug fairs to the public, dramatic art made great headway in the unity. The enthusiasm was such that some famous poets, in deference to the taste of the time, took to writing dramas. At the same time, as Wajid Ali Shah was showing his love for Rahas, Mian Amanat wrote Inder Sabha and gave performances of it in many parts of the city on several occasions. Syed Agha Hasan Amanat, popularly known as Mian Amanat (1815-1858A.D.), began as a marsiya poet but abandoned this form to write ghazals. Inder Sabha, trip Court of Indra, written in1853 A.D. is a musical comedy with dialogues in verse, and is generally supposed to be the first theatrical work in Urdu. It caught the fancy of the public. He was asked to write this comedy by Wajid Ali Shah and his flowery and artificial language is regarded as typical of the Lucknow school. Whereas the Rahas of Wajid Ali Shah was confined In the court (Shahi stage) Inder Sabha was largely produced for the public (Awami stage). The stage and scenario scripts of these productions also reveal conscious efforts at maintaining clearly-defined choreographic patterns. For instance, the entry of Indra, the hero, is described thus: “Standing behind the red curtain which used to hide the character from the view of the audience till he was introduced, Indra vibrated his bangles to the accompaniment of the rhythmic syllables played on the drums; then with the amad (a dance number in Kathak) he had to reveal his face and start a solo.” The entry of one of the pan’s is described thus: “The Pokharaj Pari enters hiding behind the curtain. After.a song heralding her entry she emerges with a graceful gat. Her beauty is dazzling now but it is irresistible when she renders the todas with brilliant technique… She finished her solo with bhava to the accompaniment of chhand, thumri and a ghazal. Thumri is to be sung only at the time of the Holi. On finishing her song she proceeds to Indra and sits beside him.” Similarly the entries and performances of other characters are given in great detail, including the procedure of the dramatic conflict. The costume and decor which are necessary to create the poetic atmosphere are also prescribed. The theme of Inder Sabha bears a striking resemblance to the theme of Vikramorvashiyam, the famous Sanskrit classic. As it was produced under Muslim patronage it assumed a Persian garb even to the extent of placing the pan (apsara) in the Caucasus. Thus when Lord Indra in his Darbar summons a par/ she comes flying from the mountains of Caucasus! According to the Persian aesthetics the most beautiful women belonged to the Caucasian region.

The Inder Sabha had attractive tunes especially composed for it and townspeople flocked to see the play. Because of Mian Amanat’s success, others emulated him and many dramas of the same nature were produced. All were called Sabha and Madari Lal and others staged many Sabhas with different versions of the same plot. They became so attractive to the people that these were the only forms of singing and dancing in which they took any interest. Old love stories were retold in pleasing verses with additional subject matter to suit the taste of the moment. Sometimes the young boys played the role of the females and danced with gay abandon. From the stage directions it is obvious that the technique of Kathak was largely used in these productions.

Apart from his interest in Rahas and other theatrical productions, Wajid Ali Shah wrote books like Banni and Najo in which he has described the technique of Kathak dance. In particular we come across the various types of the gats which he has illustrated with the help of drawings by an artist. These books were printed and published by him when he was in Calcutta after he was asked by the British to relinquish the throne and was living at Matiya Burj. The King had a press at the Garden Reach where these books were lithographed. They are rare books and are found in private collections of individuals and some museums. There are sixteen illustrations in Banni with the description and names of the gats. They are Salami Gat, Dahina Hath Gat, Bayan Hath Gat, Fariyad Gat, Muaddab Gat, Naz Gat, Gamzah Gat, Peshwaz Gat, Mukut Gat, Lucknow Ghuo-ghat Gat, Radha Ghunghat Gat, Banfala Ghunghat Gat, Bandhi Salami Gat, Dahini Banki Gat, Bavin Banki Gat, and Pyari Gat. Besides, there are references to Machahari Gat, Bhenga Gat, Thenga Gat, Lahanga Gat, and Pnnkha Gat and so on. Besides Uanni, Wajid Ali Shah has mentioned a few gats in Gunch-e-Raga and Saut-uI-Mubarak and two other works on music. Wajid Ali Shah’s interest in music was equally deep and the development of light classical and instrumental music took place during his reign as much as the development of the art of dance. Thumris are short love songs expressing romantic longing. It developed as a style of both vocal and instrumental music where parts of different ragas were joined in a rhythmic pattern. It had been already known in Benaras but was popularized by Wajid Ali Shah. Some other members of his court who followed his example were Nawab Wazir Mirza Qadar, Nawab Kalbe Ali Khan, Binda-din, Binda and Lallan, thus establishing the Lucknow style of thumri singing.

The expressional aspect of Kathak — the nrirya section — received detailed treatment with the introduction of the thumris. The songs provided the dancer enough scope for sanchari bhava, the variations and different interpretations of the poetic content. Kathak already had in its nritya aspect this element, but with the introduction of the thumris, dadras, and ghazals in dance it provided additional scope for bhava badhana – to demonstrate the skill of interpreting the meaning of the songs in many ways. Since the compositions leaned very heavily on amorous themes it developed a sensuous character more in keeping with the taste of the court and the King. Though Muslim, Wajid Ali was not averse to the songs of Krishna and Radha, for they too dwelt on shringara, the erotic sentiment underlying which were the dominant elements of spiritualism and religiosity. The nazakat, delicacy and khubsurati, the beauty of the school of Kalhak developed during this period.

The nritta aspect of Kathak was, as was natural, receiving sufficient attention on account of the element of virtuosity. A skilled dancer in nritta received more praise for the virtuosity in execution of difficult todas, tukdas and parans. The pakhavaj was replaced by the tabla and new bols were created, which showed the range of creativity on the part of a gifted percussionist and a dancer. Even in a presentation of a Rahas. Wajid Ali Shah, as noted earlier, used various elements of nritta. Emphasis was laid an clear execution of the mnemonic syllables like and ghidnag through the clear footwork that would match the distinct bols of the syllables, underlining the difference between the two consonants ka and gha! We gather from the contemporary accounts of the performances of Bindadin that when he was only nine years old he was made to practise the bols tig da tig di for four years! There is also a reference to his executing ghumkittak bols in doon through the ghunghroos (ankle-hells) when challenging the renowned pakhavaj player Kodau Singh in the court of Wajid Ali Shah.

Another noteworthy feature was layakari. Chaushashthi ka baj aspect of mridanga was in vogue. A toda was performed in thah which began with 1/4th laya and gradually increased 1/4th matra till it was taken to 64 times laya. It is known in technical parlance as darJa-ba-darJa. It is said that Nisar Ali Khan, a pakhavaj player in the court of the Nawab, was taught fifty-two types of laya in dhima tritala. However, what was noteworthy was that even when executing these variations in slow tempo or fast tempo the delicacy was not lost. It was the hallmark of the Lucknow gharana. It appears that during the reign of Wajid Ali Shah the gats in Kathak received a great attention at the hands of the dancers. Gat is understood in technical terms as Gati or chal, the graceful movements. They are not only graceful in their execution but also suggest the state of the nayika and are expressional in nature. With this overemphasis on the gats every expressional number, as it can be made out from the references in Kanun-e-Mausiki, was referred to as gat. Even the twelve thaats are called gats in the said text. The thaats mentioned are Janashini thaat and Mirabai thaat. The terms thaat and gat are used as interchangeable. Sadik Ali Dahalvi mentions that during the reign of Akbar there were the graceful walking named after the walk by the begums. The feminine walks were called Zanana nirat and the masculine were called Mardana nirat. This aspect of dancing seems to have continued in the gradual development of Kathak during the rule of the Nawabs of Avadh also. The Ritikala poetry also seems to have had its impact on these developments. As the gats demonstrated some of the states of the nayikas in love and various moods, the depiction through such expressional numbers was suggestive of such states. The Lucknow gharana excelled in depiction of these states in gat nikas where the walks were presented with delicate and refined movements. The dancer used the art of suggestion, in particular, with expressions on the face. The eyes also played a great role in augmenting the bhava. And the body followed it enhancing the impact of such subtleties. These details regarding the names of the gate are indicative of the expressions, sentiments and themes they depicted. They show also the extent to which Kathak teachers and creative dancers were exploring the content of the nritya. The Lucknow gharana excels in bhava and gats. In short in nritya.

The art indeed appears to have reached its zenith as there was great royal patronage and the dancers were amply rewarded for their art. They were looked after properly and there was a lot of leisure time at their disposal. We gather from various accounts, written during the period and after, about some of the well-known dancers and musicians who had achieved both fame and name for their talent and art. In Hanni we find the names of the following dancers and musicians who were in the court of Wajid Ali Shah: Kavam Khan, Kalandar Baksha, the dancer who was also employed to train the begums; and Haider Ali, the dancer, Mohammad Hussain, Bishan, and Gulam Abbas were dancers and some of them taught the begums in Pari Khana for the performances of Rahas and for various solo numbers. Haider Khan, Taj Khan, Inayat Khan, Kajal Hamam and Ahmad Khan were the singers and musicians. Nisar Ali Khan used to play pakhavaj whereas Khwaja Baksha was a renowned tabla player. Maadan-ul-Maushiqui mentions Lalluji of Lucknow, Prakashji, a superb dancer, Mansingh and his brother, Gamme Khan’s son and Shadi Khan’s disciple Parasadu of Benaras, Beni Prasad of Benaras, Ramasahay of Handiya who later on settled in Banda, Ramzani of Moha, Hussain Baksha and Kayam Ali of Lucknow, Mirza Wahid of Kashmir and Wajid Ali Shah’s disciple, one Kanhaiya. The last named migrated to the court of Yusuf Ali Khan. He is also reported to have sought the patronage of Maharaj Khanderao of Baroda. The famous courtesans of this period are also mentioned as follows: Gulbadan of Benaras, Sukhabadan Benaraswali, Adhvan Unnav nivasi, Jan Baksha Bandawali, Chandrabai Akbarabadwali, Jattobai Masturwali, Bi Lutfan, sister of Kochakbai. Sharar mentions Zohra and Mushtari who were not only poetesses and accomplished vocalists but were also incomparable dancers. And Jaddan the famous courtesan had entranced people for a long time with her dancing and singing.

The courtesans of Lucknow were usually divided into three categories. The first were the Kanchanis, women of the Kanchan tribe, who were actually harlots and whose primary and regular profession was to sell their virtue. They were actually inhabitants of Delhi and Punjab, at the time of Shuja-ud-Daula. Most of the well-known prostitutes of the town belonged to this category. The second category were the Chunawalis. Originally their work was to sell lime but later they joined other groups of bazar women and became quite well-known. Chunawali Haider who was renowned for her voice, belonged to this category and collected a large group of courtesans of her caste. The third category were Nagarnt, from Gujarat area. These three classes were the queens of the bazar. They established themselves and worked in groups. In addition to those courtesans who sang and danced, another group of similar character developed in Lucknow, who were the courtesans of the Pari Khana of Wajid Ali Shah. These courtesans were peculiar only to Lucknow and they performed Rahas.

The palace Chhatar Manzil of Wajid Alt Shah used to resound with dance and music. The life led by the Nawab and his associates was that of a leisurely pastime and huge amounts were spent on satisfying the Nawab’s whims and on the women around him. Naturally the British resident took a different view of the whole situation and informed the British Government in England of the local state of affairs. The Board of the East India Company decided to include Avadh in the region under British control. Wajid Ali Shah was asked to surrender. He was allotted a sum of rupees twelve lakhs a year. The King made every effort to exonerate himself but to no avail. His mother, chief consorts, and a retinue of his faithful friends followed him to Calcutta where he settled at Matiya Burj and died in the year 1887.

But the art of Kathak as it developed in Lucknow continued to flourish and even as we see its course we realize that so many factors have contributed to its growth. The exceptional Kathak dancers in Wajid Ali’s court, his own aptitude for dance and enactments of Rahas, the emergence of Inder Sabha performances, theatrical presentations and the class of the courtesans who practised the art of dance, all sustained the tradition along with the introduction of musical forms like thurnris. dadras and ghazals which gave scope for abhinaya and which indeed became the forte of the Lucknow gharana. Bindadin Maharaj’s nephews carried on the tradition in the twentieth century and during the changing times and under different patronage enriched the form with their individual gifts.

Acchan Maharaj was born in 1883 and passed away on 11th May 1947. His original name was Jagannath Prasad. He trained his two younger brothers Lacchu Maharaj and Shambhu Maharaj. Though of a heavy and unwieldy build, he was extremely gifted and while performing transformed into a different person, the very model of agility and grace. He excelled in bhava, the forte of the Lucknow gharana. He served in the court of Raigarh where he trained Kartik and Kalyan. He was for more than two decades in the court of Nawab of Rampur. He was invited to teach in Delhi by Nirmala Joshi in 1936 when Delhi School of Hindustani Music and Dance was started. The first batch consisted of the Joshi Sisters, Nirmala and Uma. Malyashri Sen. Reba (Vidyarthi) and Deepa Chaterjee and Kapila Malik (Kapila Vatsyayari). They were the first students of Acchan Maharaj in Delhi. Many other dancers like Sitara, Tara and Alaknanda, Damayanti Joshi, Vikramsingh from Ceylon, Mohanrao Kalyanpurkar and others studied under him. Acchan Maharaj was a genial soul. He had three wives and by the third wife Mahadevi he had four children, Saraswati, Vidyavati, Chandravati and a son Birju Maharaj.

Genealogy of Lucknow Gharana

Shambhu Maharaj the youngest brother was the most charismatic. A legend in his lifetime, he excelled in bhava and in recent memory he has been hailed as a superb exponent of abhinaya. He had a mellow voice. He studied thumri under Ustad Rahimuddin. When Acchan Maharaj and Shambhu Maharaj performed together people never tired of seeing them. He evolved a style of singing thumri and doing abhinaya to it while sitting on the stage and covering his feet with a shawl. He would recite a stanza and taking individual words he would do abhinaya in his apparently inexhaustible vocabulary. He brought great imagination to his interpretation which spellbound the audiences. The great Balasaraswati admired his art in unequivocal terms.

He was brought to Delhi to teach at Bharatiya Kala Kendra where he trained a number of Government of India scholarship holders. His first student among them was Mava Rao. His students are legion and there is hardly any leading senior dancer who has not studied under Shambhu Maharaj for some time. He trained his two sons and a daughter when they were young.

The contribution of Acchan Maharaj, Lacchu Maharaj and Shambhu Maharaj has been singularly significant. And Birju Maharaj continues to enrich the tradition with his abundant gifts. Krishna Mohan and Ram Mohan, his two sons, are studying under Birju Maharaj. Shambhu Maharaj received Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1955 and was made a fellow in 1967. He was afflicted with cancer and passed away on 4th November, 1970. He had a flamboyant temperament and a knack of making himself famous by his idiosyncrasies. But the world of dance and dancers accepted all his whims and pampered him. So great was his art that public forgave him all his weaknesses and foibles and accorded him the privileges of an exceptional artist.