Like in several other parts of India the arts of classical dance and music developed in Rajasthan from the 11th century A.D. From Narwar (Gwalior) a Kachhawaha’ prince established a principality and made Amber his capital. It was customary to support the bards, the artistes, the musicians and dancers, the craftsmen and artisans in the principality. They performed various duties for the chief and his court. The painters

painted portraits of important events; the charanas (the bards) recited poems and eulogized the chief and his ancestors; the musicians and dancers entertained by performing in the court and the artisans had different duties assigned to them to provide artifacts and objects of utility for the families of the ruler. Amber became politically important through contact with the Mughals in the second quarter of the sixteenth century and the royal family of Amber became predominant politically by accepting friendship of the Mughals. Amritrai, a poet who was a contemporary of Raja Mansingh I, composed in 1585 A.D. Manacharitra which mentions the use of musical instruments in the palace of Amber. That the arts of music, dance and drama were flourishing is borne out from the literary compositions of the period and the references found therein. Another work also named Manacharitra composed by Narottam Kavi and copied in 1640 A.D. by the scribe Manohar Mahatma who was in the service of Raja Jai Singh refers to raga chitras painted on the walls of Amber palace and the pothikhana collection has Mohan Kavi’s Sanskrit drama Madan Manjari which was staged for Raja Mansingh at Amber. Both Mansingh and his younger brother Madhosingh were patrons of music, dance and other arts. The renowned musician poet Pundlik Vitthal, the composer of Nartananirnaya treatise on dance, was a resident of Khandesh in the Deccan and was in the service of Sultan Burhan Khan. In 1655 AD after Khandesh was annexed to the Mughal Empire, Pundlik Vitthal came to the Mughal court where he met the Kachhawaha princes Mansingh and Madhosingh. He composed Ragamanjari under the patronage of Madhosingh.

The tradition of dance and music was thus well established and it was encouraged by the successive rulers. During the reign of Maharaja Ram Singh another text related to dance called Hastakaratnavali was composed in 1673 A.D. Ram Singh also maintained dancers who were called as paturas in his harem. Paturas were the dancing girls employed in the zenana and sang for the king and the ladies of the house. These dancers did not marry and followed the tradition of singing and dancing for the kings and their household. They used Rai as their surname and some of them who were very erudite composed poetical works also. Krida V/noda by one Mohanrai was composed for Maharaja Ram Singh.

Besides the courtesans in the zenana there was a class of courtesans who sang and danced in the court in front of the courtiers and the king and also royal procession. Sometimes these courtesans were allowed to enter the harems as concubines and to live in palaces and pleasure gardens of the princes. Dastur Komwar records a large number of courtesans who were on regular pay roll and reward list of the state of Jaipur. We come across names of some of the courtesans like Anandrai, Uttamrai, Gulabrai, Chandhalrai, Jonrai. Kishorerai, Kishoro Beli, Khumani, Goviridi, Diljani and Nritya Vilas. These dancers and singers had very close relations with the ruling chiefs. Maharaja Ram Singh was very close to a temple dancer Chandra of Ramachandra temple. Jadonji was very powerful as can be gauged from the fact that she was an important factor during the adoption of Sawai Mansingh II. There was one Rasakapoor, a courtesan who rose to such eminence with Maharaja Jagat Singh that she literally had her say in the affairs of the State. The records of Rajasthan Devasthan Department reveal that some women dancers were attached to the temple of Govind Deoji to sing and dance before the idol daily for which a yearly stipend was paid to them.

From the number of manuscripts collected in the pothikhana at Jaipur one can assess the encouragement given to dance and music by the Amber rulers. Most of the treatises in Sanskrit dating from the fifteenth century are on music with a specific section on dance. Sangita has been defined as an art where song, instrumental music and dance find a fine blending. Ashokamalla’s Sangita Kalpataru (1494 A.D.), Mohammed Shah’s Sangita Mallika (1653 A.D.), Sangita Ratnakar KalanidhiofKattinath (1677 A.D.), Sangita Madhavamby Prabodhananda Saraswati, Sangita Ratnakar Rasa Pradipa by Nurkhan and Hastraka Ratnavali by Raghava (1673 A.D.) speak volumes for the rulers’ love and understanding of the classical performing arts.

Another interesting feature of this period is the commissioning of the raga chitras, paintings based on musical mode and ragas and raginis. One such among a series is dated 1709 AD. written by Rama Krishna Mahatma, at Ambavati Fort during the reign of Maharaja Jai Singh. As can be seen by the study of these paintings the figures often reveal the postures of dance suggesting the interrelationship and understanding of the arts that existed among the artistes practicing different forms. The arts received a great fillip during the reign of Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh. He ruled over Rajasthan from 1699 A.D. to 1743 A.D. and during his time Amber State expanded manifold. He is well known in history as founder of Jaipur. His intellectual attainments naturally gave him a sense of superiority in dealing with persons who had even more influence with the Mughals. But his farsightedness and extremely diplomatic relations with the Mughals helped him maintain his superiority. However, he was an extremely modest person and would take great pains to reply to a poor scholar from Karnataka or Bengal, and would visit the poets and scholars in Brahmapuri, the residential locality he had built for them in beautiful surroundings, unannounced and would pass many hours with them. It is said that without Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh’s knowledge or goodwill nothing happened in Rajasthan and his advice was sought not only by the princes of Rajputana, but also of Bundelkhand and Malwa. His outstanding contribution in the field of culture covers a wide range of subjects including astronomy, town planning, architecture, fine arts, music, dance and literature.

We gather from records that in 1714 A.D. he had Pandit Jagannath, a Maratha Brahman, appointed to teach him the Vedas. Jai Singh had a great aptitude for mathematics and astronomy and was called Astronomer Prince. The observatories built by him are living monuments to his abiding passion for astronomy. Jaipur which was called Jainagar remains to this day a beautiful and well laid out city. Jai Singh received great assistance from an architect Vidyadhar Chakravarty who was appointed in 1728 A.D. as Divan-Desh. The palace complex consisting of spacious squares, Diwan-i-Am, Diwan-i-Khas and Chandramahal and the pathways which extend to the Govind Deo’s temple up to Badal Mahal are a tribute to a King for his elevated sense of aesthetics and love for architectural beauty. We come across references to the temple dancers attached to the Govind Deo temple, and though specific names of the dancers are not available, it gives us an idea about the patronage extended by the King. He was a devout Vaishnava and was religious by temperament. He performed all the srausrauta yajnas, including the Ashvamedha.

Though a great many details are available about the musicians, very little is available about the leading dancers of the day. However, the patronage was extended to all sorts of artistes and since there was a tradition of a community called Kathak who performed dance it is very likely that the dance as an art form was equally patronized. The Kathak community lived in Churu-Sujangarh area nearby and about Shekhavati in the sixteenth century. During the reign of Akbar many Shekhavati sardars took up service at the Mughal court. When the Rajput sardars and patrons moved lo the Mughal court, with them went the musicians and dancers also. They naturally came in contact with the Mughals and received patronage from them. Since the Mughal court was prosperous and cultured these artistes also flourished. But it all changed during the reign of the Mughal king Aurangzeb and after the death of Mohammed Shah Rangile in 1748 A.D., the musicians and dancers once again migrated to centers like Lucknow, Murshidabad, Alwar and Jaipur.

At the Gunijankhana the artistes had different categories. They were the employees of the Gunijankhana and had to report daily. The great artistes of outstanding merit were not required lo present themselves daily but only on important occasions and whenever the Maharaja called them to play for him or the guests. The officer in charge of the Gunijankhana had to be informed in case they were to go to other courts when invited to perform there. In case of others they had to come daily and play or sing at the Hara BungLa, the green balcony, where music was played the whole day as was the practice then. From the records it is gathered that during the rule of Maharaja Ram Singh there were one hundred and sixty artistes employed. Their widows after the death of the artistes were also supported and received pension. It was during the time of Maharaja Sawai Madho Singh that there were celebrations of festivals like Ganga Saptami, Ganga Dashmi and Radha Ashtami, as the king was a devotee of Ganga besides being a devotee of Krishna. He continued the institution of the Gunijankhana. That ensured financial support and security to the artistes.

While reconstructing the history of Jaipur gharana with the background of the royal patronage and some of the social institutions, it is also necessary to take into account the evidences provided by the charanas—the bards who preserved the family history. Though Jaipur gharana nomenclature has definite geographical connotations the families which carried the tradition of dance have been the natives of the Bikaner State in the western part of Rajasthan and also those from the areas near Churu, Sujangarh and Shekhavati region. Some of the information about the Jaipur gharana is supplemented from the oral history tradition and details given by the performing artistes a quarter of a century ago. By now they are all dead. In the years immediately after Independence some of the leading exponents when approached by some scholars have given information based on their memory and details provided by the family bards. A detailed work and research in the archives of Jaipur and Bikaner may provide some more information and it is possible to reconstruct the line of the dancers who were in the court of some of the rulers who extended their patronage to the musicians and dancers.

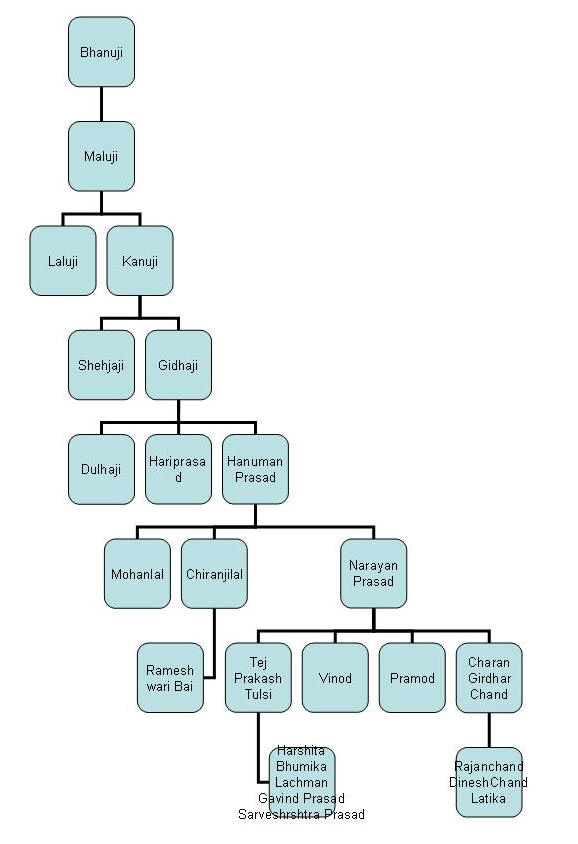

From the documents in the possession of Mohanlalji, eldest son of the late Hanuman Prasadji of Jaipur and on the strength of the oral history from the family bard Pratapji, one is able to construct some plausible history of the exponents of the Jaipur gharana. This takes us as far back as one hundred and eighty years approximately.

The earliest name in living memory is that of Bhanuji who was a devotee of Shiva. He is said to have learnt Shiva Tandava from some saint. He passed this art to his son Maluji. Maluji had two sons, Laluji and Kanhuji. They too learnt Shiva Tandava from their father Maluji, continuing the family tradition. It is said that Kanhuji went to Brindavan and learnt the dances centering around the Krishna theme and enriched his repertoire with Lasya, the graceful aspect of dance. Kanhuji had two sons, Geedhaji and Shehjaji to whom he passed on his art. Geedhaji specialised in Tandava and Shehjaji in Lasya aspects of the dance. Geedhaji had five sons. Of these sons, one Dulhaji went over to Jaipur and settled there. He earned fame as an expert in Shiva Tandava and also obtained mastery over the Lasya aspect. He became well known as Girdhariji though his name was Dulhaji.

From the records of the Gunijankhana of Maharaja Sawai Madho Singh II we learn that there were ten male Kathak dancers serving in the department Besides there were thirty-eight female singers and dancers, twenty sarangi players and sixteen pakhavaj players to accompany them. Before the merger of the State in the Indian Union the following dancers were in the employment of the Gunijankhana: Shyamalji and his son Nathu Lalji, Badri Prasadji, Chunnilalji, Lakshmi Narayanji, Chhajulalji; the female dancers were Gauhar Jan, Kamarjan, Sardar of Sambhar and her daughter Kamala, Dhannibai, Ratan and Maina. They became quite famous and were often invited by other royal families. With the closure of the Gunijankhana the artistes migrated and sought patronage in the music schools or gave private tuitions and took up jobs at the radio stations since after the merger of the State the court did not support them.

This brings us close to the present century. As can be seen from the genealogical tables Girdhariji had two sons: Hari Prasad and Hanuman Prasad. The former had no issue. Hanuman Prasad had three sons: Mohanlal, Chiranjilal and Narayan Prasad. Mohanlal was adept in music and had deep knowledge of dhrupad. He taught for some time at Khairagarh University in Madhya Pradesh. Chiranjilal taught at Gandharva Mahavidyalaya in Delhi, so did Narayan Prasad. Hari Prasad and Hanuman Prasad used to perform together and were popularly known as Deo Pari Ka Joda. Their duets were replete with elements of virility and grace. From this account it is possible to surmise that Jaipur gharana exponents gave due emphasis to forceful and graceful dancing. These two brothers had cousins in Shyamlal, Chunnilal, Durga Prasadji and Govardhanji who were brilliant dancers. They had the good fortune of learning from one Shankarlal about whom nothing is known except that his daughter’s son, one Badriprasad, distinguished himself as a Kathak dancer. Shankarlal was also a gifted thumri singer. All these performers, Hari Prasad and Hanuman Prasad, their cousins Shyamlal, Chunnilal, Durga Prasad and Govardhanji earned fame as brilliant exponents of Jaipur gharana.

The names of Ghunnilal’s two sons Jailalji and Sunder Prasadji have become household words. We do not know much about Shyamlal who had a son named Sheolal who is a music composer. Durgalal had no issue. Govardhanji’s son Khemchand Prakash was a fine music director whose music in films earned him good name.

Besides Jaipur we have some information about other states where institutions similar in nature to Gunijankhana of Jaipur were maintained by the princely states before they merged in the Indian Union after Independence. For instance, in Udaipur it was called Sangita Prakash which was looked after by the chief whose designation was Hakim. It was his job to consider the applications of the musicians and dancers who wished to perform in the court. He used to be a knowledgeable person who could judge the merit of the artistes. Sangita Prakash was started by Maharana Sajjan Singh. During the reign of Maharaja Bhupal Singh it was Hakim Pannalalji Masani who was in charge of the Sangita Prakash. The Maharaja used to give financial rewards to the deserving and gifted artistes. There was one Kathak dancer by the name of Pyarelal who was very talented. He stayed in Udaipur for six or seven years. He danced regularly for the Maharana. There was one pundit from Benaras whose Shiva Tandava is still remembered by some elderly people in Udaipur. He had an accompanist in Jailal who was an excellent harmonium player and had a rather thin voice. Pannalalji Masani’s father too was a Hakim and he remembers having attended the musical soirees of the musicians and dancers from Jaipur and Jodhpur, Benaras and Bikaner.

Besides the musicians and other artistes, famous courtesans called tewaifs used to visit the court of Udaipur. They used to sing and also perform Kathak dance. Some tawaifs used to take out a swang called tutiyan after the ghingh gangaur festival. One tawaif used to dress like a man with a turban and held a sword in her hand. The other impersonated as his wife and performed mujra. Besides the tawaifs there used to be dholanias who were singers. Some of the tawaifs of Udaipur were well known for their art.

Though there is no written record available the contemporary gurus of Jaipur gharana maintain that a meeting of the kathakas took place in 1895 A.D. during the time of Maharaja Sawai Madho Singh in Jaipur to drown all the differences about the gharanas. Earlier the kathakas in Jaipur belonged to one Sanwaldasji’s gharana. There used to be as many gharanas as there were gurus and they were known by the gharana named after the guru. This caused sufficient confusion and hard feelings as most of the exponents belonged to the same group. In this historic meeting exponents from Lucknow were also invited. It was resolved that instead of giving names to the gharanas after the individuals, they be given name of the place. This practice is followed in classical music. For instance, Jaipur gharana, Punjab gharana, Atrauli gharana. Thus the two major gharanas came to be known by that time as Lucknow gharana and Jaipur gharana. There is a third gharana known as Janaki Prasad gharana which even now in some circles is known as Benaras gharana. As a matter of fact Janaki Prasadji hailed from Bikaner. In this meeting it was decided to give titles like Maharaj to the guru who had more than one hundred disciples and at that time Bindadin Maharaj was awarded this title as he had a large number of students studying under him in Lucknow. There were other titles like Nayak and Pandit which were given to Shankarlalji and Sukhdev Prasadji of Bandwa. For Janaki Prasadji the title of Maharaj was decided, but he could not attend the meeting. It is also said that four young dancers from Jaipur gharana were sent to study under the guidance of Bindadin Maharaj and they returned from Lucknow after a period of apprenticeship of six months. At that time some kathakas opposed their doing so accusing them of lowering the standards of Kathak as the Lucknow gharana was influenced by the taste of Muslim rulers.

We gather some important geographical distribution of the kathakas from the details prepared by Pandit Gaurishankar. It suggests the popularity of Kathak and also the patronage these artistes received in various parts of the country. Some Kathak dancers migrated for earning livelihood and those who had tenacity succeeded in having some following of the students. It gives us only an idea about the state of Kathak and the artistes who followed the Jaipur gharana. Among the contemporary gurus and performers of the Jaipur gharana, Jailal. the doyen among them, was born on the day of Basant Panchami in the year 1885. His training began from a very young age. His taiyyari was exceptional and he drew attention of all for his natural gifts. The Maharaja of Jaipur was very fond of him. He gave a place of honor to Jailal in Gunijankhana, where seven hundred and fifty artistes were maintained. Jailal later on spent eight years in the court of Raja Chakradhar Singh at Raigarh and trained Kartik and Kalyan. He married twice and had a son and a daughter by them. Ram Gopal and Jai Kumari were step children. Both were trained by Jailal. In his last years Jailal was in Calcutta teaching at Bani Bithi Vidyalaya. Ram Gopal also taughl Kathak in Calcutta and Cuttack. His daughter Kajal Misra is a fine dancer. His son Rajkumar plays tabla. His wife Susmita Misra along with Kajal and Rajkumar runs a dance academy in Calcutta. Jailal died on 19th May 1945 in Calcutta.

Sunder Prasad, the younger brother of Jailal, was trained by their father Chunnilal. He was sent at a very young age to Lucknow to study under Maharaj Bindadin. Thus he had good knowledge of Jaipur and Lucknow gharanas. In the thirties Sunder Prasad established Maharaj Bindadin School of Kathak in Bombay. He was in Bombay for more than twenty years. He trained several dancers which include Mohanrao Kalyanpurkar, Poovaiah Sisters, Sunalini Devi, Shirin Vajifdar, Madame Menaka, Sohanlal, Hiralal and Roshan Kumari. For some time he was in Madras. He settled in New Delhi in 1958 and joined Bharatiya Kala Kendra. He trained practically every leading dancer who came to study as Government scholar and as a student at the Bharatiya Kala Kendra. Well known among them are Uma Sharma, Urmila Nagar, Maya Rao, Kumudini Lakhia, Durgalal, etc. He received Sangeet Natak Akaderni Award in 1959. He passed away on 3()th May 1970.

Narayan Prasad was indeed more famous than his two elder brothers, Mohanlal and Chunnilal. Though he died at the young age of forty-eight on 12th September 1958 in Delhi, he had received a great acclaim for his talents. His professional career had begun when he was only eleven. His performances all over India in various conferences at Jaipur, Raigarh, Allahadad, Baroda and Ajmer were a great success. He too was attached to Gunijankhana at Jaipur. His dance style was unique. His manner was chiseled and there was no hurry or impatience in his exposition. His performances were noteworthy for the element of dignity. He could negotiate difficult talas like Lakshmi tala, Brahma tala and Dhamar. His chakkardar parans in Eka tala known as bedam, as they did not permit any respite between sub-sections, were justly famous. His nav-ki-gat, the movements of the boat, mesmerized the audience into a feeling of gently flowing along with his dance. He was an accomplished vocalist. Among his students, BabuIal Patni of Jaipur, Kundanlal Gangani, his nephew, Shankarlal Jha of Dehradun. Shakuntala Jain and Pushpa Batra are well known, whereas Rani Kama has been hailed as his famed disciple since she had an intensive training under him. He taught for more than twelve years at Gandharva Mahavidyalaya in New Delhi.

Ram Copal, the only son of Jailal of Jaipur gharana, was born at Raigarh when Jailal was at the court of Raja Chakradhar Singh. He was trained by Jailal and besides performing he taught at Bani Bidya Vithi School at Calcutta and at Kala Vikash Kendra, Cuttack. His daughter Kajal Misra and son Rajkumar Misra have studied Kathak under him. Rajkumar is a fine percussionist and accompanies Kajal Misra in her Kathak recitals. With their mother Susmita Misra they run an academy of dance in Calcutta.

Jai Kumari, daughter of Jailal was trained by her father in Jaipur gharana technique. She had reached such proficiency in her art that at one time very few dancers could compete with her. Her performances at the All India Dance and Music Conferences were dazzling and she was hailed as a brilliant star in the firmament of Kathak. After Jailal’s demise she gave up dancing and taught at Bani Bithi Vidyalaya at Calcutta. A few years ago she retired to Baroda where she died of cancer.

Sohanlal was trained by Jailal of Jaipur gharana. He also studied under Sunder Prasad and Devilal. He settled in Bangalore and established a school called Vishwakalasthan in 1942. He is credited with the pioneering work of introducing Kathak in the South. Among his early students were Maya Rao and her sisters. He shot into prominence after his tour abroad with Ram Gopal. His dance compositions like Vayu, the Wind God, The Dream of Mira and Prabhat Nritya are famous.

When young, Kundanlal Gangani, a nephew of Narayan Prasad, was in the Darbar of Raigarh. He was trained by Narayan Prasad and was exposed to the training of Jailal and Acchan Maharaj at Raigarh. He gave several performances in Bihar and Madhya Pradesh. In 1953 he joined the Department of Dance at the M.S. University of Baroda. At the time of his death in 1984 he was on the faculty of Kathak Kendra, New Delhi. His two sons Rajendra Kumar and Fateh Singh were also trained by him.

Sunderlal, brother of Kundanlal, is also a noted Kathak dancer and teacher. He hails from Sujangarh in Rajasthan. He was trained by Jaipur gharana masters like Sunder Prasad, Gauri Shankar, Shiva Narayan and Hazarilal. He has been with the Department of Dance at the M.S. University of Baroda since 1951 and has trained several students among whom, besides his two sons Jagdish and Harish, Prafulla Oza and Anjani Ambegaonkar are well known. He has composed many kavits, todas, tukdas. thumris and bhujans. He is also an excellent tabla player.

Gaurishankar hails from Bikaner. His father Devilal was a noted Kathak. Besides studying Kathak under his father he also studied under Sunder Prasad and uncle Shivlal. He drew attention by his appearance at the Allahabad Conference in 1934. He joined Madame Menaka in 1936, toured with her in Europe and partnered her in the dance-dramas like Devavijayanritya and Menaka Lasvam. He won the highest prize in Germany at the International Dance Olympiad in Berlin. In 1938 he joined Santiniketan and worked with Gurudev Rabindra Nath Tagore for some time. In 1942, he again joined Menaka at Nrityalayam and after its closure started his own school in Bombay called Prachin Nritya Niketan. He has choreographed many dance-dramas. With the establishment of Kathak Kendra at Jaipur, at present he is on its faculty teaching Kathak.

Among other Jaipur gharana exponents and teachers mention must be made of Hanuman Prasad, son of Gangaram, who taught at the Hill Grange School in Bombay. His nephew Trilok Prasad continues teaching there. Ganesh Hiralal, son of Hiralal, teaches at Bombay at Kala Jyoti. Among others from Jaipur gharana, Hazarilal, son of Hanuman Prasad, taught at Bhatkhande Sangeet Vidyapith in Lucknow, Sohanlal, a relation of Jailal, runs Jailal Lalit Kala Academy in New Delhi, Bansilal teaches at Shri Ram Bharatiya Kala Kendra, New Delhi and Radhelal’s sons Anokhelal and Krishna Kumar teach at Springdale and Delhi Public School respectively.

Genealogy of Jaipur Gharana

Narayan Prasadji’s dancing was noteworthy for chakkardar parans in eka tala which allows no respite between the sub-sections commonly called bedam parans, and which by just varying their manner of movement can be danced in different talas without losing any of their bols (mnemonic syllables) or textual syllables. Three such successive counting of eight, the first one is danced in vilarnbita, the second in madhya and the third in druta, with the last one landing immaculately on a sam and adroit manipulation of laya in terms of patterns of anaagat and ateet variety, were highlights of his nritta.

Today the differences between the Lucknow gharana and the Jaipur gharana are at best seen in renderings of gifted dancers like Birju Maharaj and Roshan Kumari. One at once notices the salient features of their respective gharanas illumined in their expositions. Most of the Kathak dancers now freely use the elements of both the gharanas. But for the use of the bols, at times, it is difficult to figure out their gharana. Thus what one often watches is the bodily manipulation ang, of the Lucknow gharana which is very graceful and the execution of the lamcchad parans of the Jaipur gharana which has long bols. However the impact is pleasant and in the hands of gifted exponents the attempts at fusion of the two gharanas have found felicitous expression.